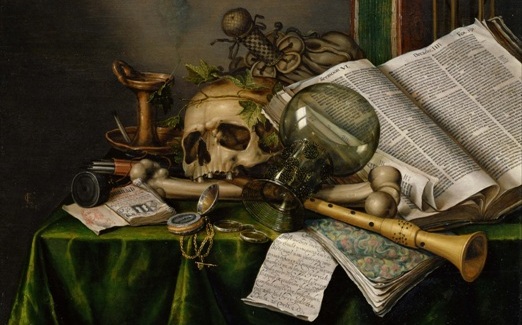

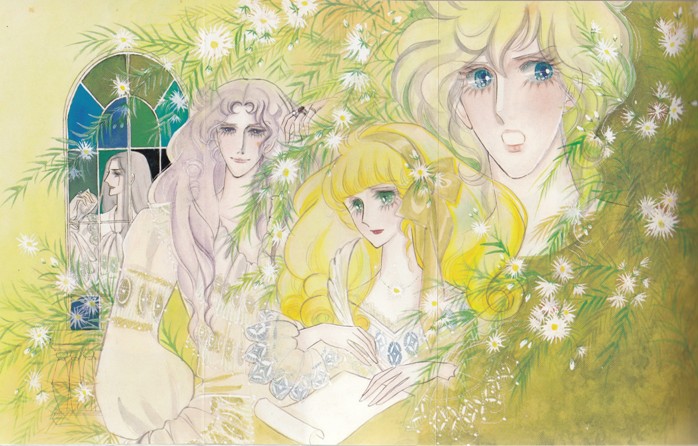

An overview of the older quotes of the month

Recapitulation of the older quotes of the month from the main page. Designation quote of the month is not ideal, because these “quotes” are actually excerpts from book series Angélique by Anne Golon, which are appropriately expressing the atmosphere of the actual period of the year. In general, all the quotes are corresponding to the current year cycle and the weather, and of course, to the cultural traditions (rites) suitable for the current season.

November 2022

In the poop stateroom of the

Gouldsboro, a brazier on a solidly-made wrought-iron tripod gave out a cosy warmth. At the far end an alcove whose brocade curtains had been raised displayed the luxuriously soft bed with its lace sheets turned down over silks and furs. The room was comfortable and equipped with all sorts of beautiful objects. The large poop windows admitted a diffuse glow from the riding-lights outside. The soft brightness sparkled upon the bronze and gold of the furniture and the costly bindings of the books that stood in rows in a rosewood case. Whenever Angélique took refuge here she invariably felt a sensation of well-being and security. She threw her cloak over the back of a chair, went into the alcove and began to undress.

(Golon, Sergeanne. Angélique and the Ghosts. London: Pan Books, 1979, p. 59)

October 2022

She was happy to leave the two babies in this vast, warm, fragrant domain. The fire was blazing in the hearth with a new ardour. (...) Florimond seemed stiffly awkward in his little grey-brown muslin frock, his yellow serge top and green serge apron. A bonnet, also of green serge, covered his head. These colours made his frail little face look even more sickly. She felt his forehead and put her lips in the hollow of his little hand to see if he was feverish. He seemed well enough, though a little fretful and grumpy. As for Cantor, since morning he hadn't stopped trying to undo the swaddling-clothes into which Rosine had wrapped him. In the basket into which he had been put he stood up, naked as a little Cupid, and tried to get out to catch the flames.

(Golon, Sergeanne. Angélique. The Road to Versailles. London: Pan Books, 1966, p. 165-166)

September 2022

The forest seemed to have a brilliant sheen which you could see even from afar, and brilliant exotic colours could be seen amongst the trees. She could make out the occasional black fir and the turquoise blue of enormous pine trees with tops like parasols, and here and there the red-gold hues of a bush heralding the autumn. Autumn already! And they had never even seen the summer. All around them, in the bay and far out to sea, leafy pink-edged islands lay in the brilliant lavender-coloured waters, their deadly reefs looking like school of sharks defending the wonderful coastline from covetous men. It seemed quite incredible that they had ever managed to slip between these islands to reach the place of safety where the ship now lay gently rocking on the waters.

(Golon, Sergeanne. Angélique in Love. London: Pan Books, 1969, p. 326-327)

August 2022

Around her the concubines were whispering and day-dreaming and intriguings as usual. All these females had abandoned themselves to the sensual passion of their lovely bodies consecrated to love. Soft and smooth, perfumed, anointed, their flowing curves were made for the embraces of a royal master. They had no other reason for existing, and they lived in the expectation of the rapture he would give them. Their inactivity and their forced continence annoyed them, for far too seldom was there one of these hundreds of women who received the royal favours.

(Golon, Sergeanne. Angélique and the Sultan. London: Pan Books, 1968, p. 311)

July 2022

As she approached the hut where Cantor was sleeping she saw his lamp shining trought the half-open sky-light and she stopped. Was he alone? Can one ever be sure with these young men! But casting a glance inside, she gave a smile. For he had fallen asleep with his hand still outstretched towards a huge basket of cherries which he had placed on a stool close to his bed. (...) She crept into the hut and sat down beside his bed. "Cantor!" He gave a start and opened his eyes. "Don't be frightened. I only came to ask your advice about something. Whad do you think about the Duchess of Maudribourg?" She had caught him unawares so that he would not have time to be put on his guard and become distant with her as he customarily was. He raised himself up on one elbow and looked suspiciously at her. She picked up the basket of cherries and placed it between the two of them. The fruit was a delight to the eye and to the palate. The cherries were huge, brilliant, and a true dazzling red.

(Golon, Sergeanne. Angélique and the Demon. London: Pan Books, 1975, p. 260)

June 2022

The evening light falling through the shining leaves of the enormous oaks that overhung the cliff, and filtering through the dense masses of verdure, had taken on a greenish tinge that made their faces look pale, and deepened the shadows. Now a golden sheen lay on the river and the little bay had darkened to the colour of copper. Thanks to the reflection of the sky in the waters, there seemed to be more light about than a little earlier. Soon it would be June, when the evenings encroach upon the kingdom of night, a time of the year when both human beings and animals devote but few hours to sleep. Someone had thrown big black mushrooms, round and desiccated like cannon balls, on the fires, where they burned giving off a bitter, woody smell which had the beneficial effect of driving the mosquitos away, and this smell now mingled with that of tobacco rising from the pipes of the men. The tiny cove was full of mist and goodly fragrance, a cosy refuge beside the Kennebec.

(Golon, Sergeanne. The Temptation of Angélique. Book two. London: Pan Books, 1971, p. 17-18)

May 2022

When people heard that a new sorceress had quietly installed herself in the Hauts-de-Mère caves, they had called her Mélusine from sheer habit. Where do these forest witches come from? What paths of misfortune and malediction lead them to these same spots, there to become allies of the moon, the screech-owl and growing things? The present witch was said to be the most learned and the most dangerous that the region had ever known. It was alleged that she treated fevers with vipers' broth, gout with salts distilled from the blood of lice, and deafness with ants' oil, and that she also knew the art of imprisoning demons from Satan's chosen legions in a nutshell. (...) Girls who were in the family way well knew the path to her lair as did also men tired of waiting for the natural death of some old uncle of whom they had expectations. Angélique, who had heard all this tittle-tattle, scrutinized the weird creature with considerable interest.

(Golon, Sergeanne. Angélique in Revolt. London: Pan Books, 1966, p. 61)

April 2022

"But where have you come from? You seem quite transfigured." "I do?" All of a sudden Angélique caught sight of herself standing there naked in front of the tall polished-steel mirror that leant against the wall. Normally she only used to glance in it absentmindedly to arrange her hair and her head-dress. In an instant she took in her white body, the very picture of healthy womanhood with its neat waist, high breasts, long back and graceful legs, 'the most beautiful legs in Versailles' with the round red scar that Colin Paturel had had to make to save her from the snake in the Riff. How she had forgotten her body! She could hear that insulting voice in her ears again: "A woman for whom I wouldn't give a hundred piastres today." She gave a casual mocking shrug. "What does he want? Ah, well, so much the worse for him!"

(Golon, Sergeanne. Angélique in Revolt. London: Pan Books, 1966, p. 371)

March 2022

"(...) Seeing you has kindled in me a flame which I thought was dead. The death of the heart is the worst thing... I would like to keep you near me..." (...) He could not understand the dilemma he was putting her in. What would she have answered, had he made his proposition to her in some other place? She did not know. But here, in this house where she found herself for the first time, she was surrounded by ghosts. Next to the Prince de Condé, risen from the past, with his slightly old-fashioned air, there stood the luminous, hard outline of Philippe in his pale satins and, behind them, a masked wraith, clothed in black velvet and silver, with a single blood-red ruby on his finger, the cursed nobleman who had been her master and her only love. Among all of them, whom life or death had set free, she alone remained a captive of the old tragedy. "What's the matter?" asked the Prince. "Why are there tears in your eyes? Have I hurt you in any way? Do stay here, where you seem to like it. Let me love you. I'll be discreet..." She shook her head slowly: "No,

it's impossible, Monseigneur."

(Golon, Sergeanne. Angélique. The Road to Versailles. London: Pan Books, 1966, p. 277)

February 2022

The air in the streets of Paris, which she had formerly found so evil-smelling, seemed pure and delicious when she found herself free at last, alive and dressed in clean clothes outside the repulsive building. She was walking almost gaily, holding her baby in her arms. (...) People passed her with tapers in their hands. A smell of hot pancakes came drifting from the houses. She told herself that this must be the second of February. People were celebrating the presentation of the Child Jesus at the Temple and the Purification of the Virgin Mary by exchanging gifts of candles, according to a tradition that had given this day the name of Candlemas. "Poor little Jesus!" Angélique thought, kissing Cantor's brow, as she passed through the gate of the Temple.

(Golon, Sergeanne. Angélique, the Marquise of the Angels. London: Pan Books, 1966, p. 508)

January 2022

They had no need of the lantern. Once out of the narrow trench that had been cut between two walls of ice from the threshold up to the hard surface of the yard, the moonlight was quite bright enough. (...) Visibility extended quite a distance, right to the far end of the nearest lake. The countryside lay shrouded in the powdered snow which the wind was stirring up from the ground, and seemed to appear through a dazzling mist that blurred its contours. It was like diamond dust forming a swirling halo round the tops of the trees, a nimbus over the curve of the hills, making the edge of the lake stand out beneath its great expanse of smooth icy snow, in which the moon was reflected, making it look more like a Silver Lake than ever.

(Golon, Sergeanne. The Countess Angélique. Ontario: Pan Books, 1968, p. 424)

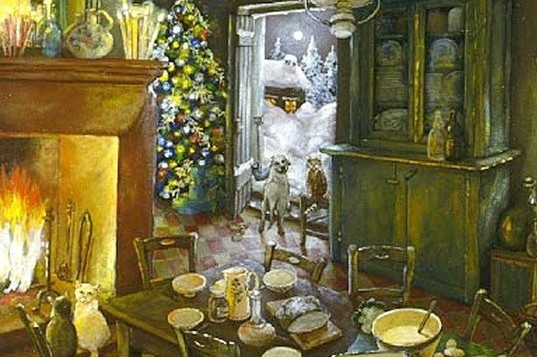

December 2021

'Take courage, my dear sister,' Raymond said gently. 'The birth of Christ brings us a message of hope: peace to men of good will.' But these alternatives of hope and despair were sapping the young woman's strength. When her thoughts carried her back to the last festive Christmas she had spent at Toulouse, she felt fllled with horror at the long way she had come since then. Could she have imagined, a year ago, that she would find herself on this Christmas Eve, while the bells of Paris were pealing under the grey sky, with no shelter other than Widow Cordeau's hearth? Next to the old woman spinning her yarn and the apprentice hangman who was innocently playing with little Florimond, she barely felt the strength to hold out her palms to the fire.

(Golon, Sergeanne. Angélique, the Marquise of the Angels. London: Pan Books, 1966, p. 423)

November 2021

The company sat down to table. It was only a small intimate gathering comprising the usual members of the Rescator's flotilla, superior officers and their more or less obligatory guests. This company had come into being from the very beginning of the journey and it formed a homogenous group despite appearances because it was made up of individuals who had undergone in this brief period the same adventures and shared, in the nature of things, the same preoccupations and the same joys. But, in honour of the wine, the table had been set more luxuriously, and before each guest had been placed goblets of Bohemian glass.

(Golon, Sergeanne. Angélique and the Ghosts. London: Pan Books, 1979, p. 226-227)

October 2021

After gazing for a moment they rode off towards the left; the curtain of trees closed behind them, and the sea vanished. Now they were surrounded by their richly-clad escort of ageless trees, arrayed now mainly in scarlet, orange and old gold. They could see a blue-green lake shining between the trees and an elk drinking at it. When it threw its head back its antlers looked like dark wings. They could never forget that behind the slim trunks of the birch trees, and behind the colonnades of oaks, lived an intensely vital animal world. There were elks, bears, stags, reindeer, wolves and coyotes, and thousands of small fur-bearing creatures: beavers, mink, silver foxes, and ermine. The trees were full of birds, too.

(Golon, Sergeanne. Angélique in Love. London: Pan Books, 1969, p. 428-429)

September 2021

In the vestibule she met Hortense, with a white apron tied around her lean waist. The house was redolent with the smell of cooked strawberries and oranges. In September good housewives make their preserves. It was a delicate and important operation, performed amid huge red copper basins, crushed sugar-loaves and Barbe's tears. The house was upside down for three days. Hortense, who was carrying a precious sugar-loaf, stumbled against Florimond, who was coming out of the kitchen, wildly waving his silver rattle with its three little bells and two crystal teeth. Nothing more was needed to make the thunderstorm break. (...) 'Don't scream so much,' said Angélique. 'There's nothing I'd like better than to help you make your jams. I know some very good southern recipes.' Hortense, sugar-loaf in hand, straightened herself to her full height, as if draping herself in the garments of a tragic actress. 'Never,' she said fiercely.

(Golon, Sergeanne. Angélique, the Marquise of the Angels. London: Pan Books, 1966, p. 344)

August 2021

Leaving the two men alone, Abigail had taken Angélique outside to show her the garden. The friendship between the two women was stronger than any quarrel. Instinctively they cut themselves off, refraining from rigid judgements in order to protect the bond of mutual affection between them. Different as they were, they needed each other's affection. It was a refuge, a certainty, a living thing that even absence could not destroy, and that every tribulation suffered and strengthened rather than destroyed.

(Golon, Sergeanne. Angélique and the Demon. London: Pan Books, 1975, p. 73)

July 2021

Angélique thought she could stay awake, but she must have dropped off for a nap, because suddenly she realised it was daylight. The shimmering light of dawn revealed an island ahead of them. In the counterlight from the pale gold, pink and light blue sky, it was only a mass of dark muddy blue reflected in the almost glassy surface of the water. (...) The Duc de Vivonne was in an excellent mood. He handed her his field-glasses. 'See how attractive that island is, Madame. Notice there is no surf at the base of those volcanic rocks. That means we will approach in complete calm. Nothing untoward to come alongside.' Angélique had some trouble adjusting the glasses to her eyes, but finally she shrieked with pleasure at discovering a cove hidden among the flowering lilacs and the seagulls swooping above them.

(Golon, Sergeanne. Angélique and the Sultan. London: Pan Books, 1968, p. 99)

June 2021

Angélique told her how the kitten had been injured. (...) Honorine listened to what Angélique was saying while keeping an eye on her rival, who was also watching her through half-closed eyes. She rubbed her cheek against Angélique's caressingly, and Angélique gave her an affectionate kiss. She looked at the wilful little face cuddling up against her and proudly stroked Honorine's copper-coloured hair. Her daughter was beautiful, and there was something of the princess in her bearing. She had a long, proud, strong neck, and her skin was not freckled, as might have been expected, but delicately golden like Angélique's. In her rounded oval face, with its well-shaped features, her small dark eyes were the only feature that would have seemed unattractive if their fearless, earnest expression had not impressed those on whom she fixed her cool, shrewdly watchful gaze. She was quite a character.

(Golon, Sergeanne. Angélique and the Ghosts. London: Pan Books, 1979, p. 45-46)

May 2021

With one arm around the shoulders of her two little boys, Angélique breathed with delight the pure air of the flowering countryside. She wondered how she could have lived for so many years in a city like Paris. She gave shouts of joy and named the hamlets they were passing through, each of which recalled to her mind some incident from her childhood. For days, she had been giving her sons detailed descriptions of Monteloup and the wonderful games one could play there. Florimond and Cantor knew all about the underground passage which used to serve her as a witch's cave, and about the loft with its enchanted nooks and crannies. At last Plessis loomed up in the distance, white and mysterious on the edge of its pool. To Angélique, who had meanwhile known the sumptuous abodes and palaces of Paris, it seemed smaller than the image engraved in her memory.

(Golon, Sergeanne. Angélique. The Road to Versailles. London: Pan Books, 1966, p. 321-322)

April 2021

'I must admit that women can be pretty mad, but you undoubtedly have overstepped the expected limits by a very long way. Let us take a look back: the last time I met you, you left me, by way of reminder, with my xebec on fire and with a debt of thirty-five thousand piastres. Four years later, it seems perfectly natural to you to come and see me, without in the least fearing any reprisals, and ask me to take you on board my ship with forty fugitive friends of yours. You must admit that this is a somewhat outrageous demand.' With a flick of his finger he upturned an hour-glass that stood beside him on an occasional table. The instrument was held in place by its heavy bronze pedestal and did not rock about as the ship pitched and tossed. The sand began to run through it, and cascaded down in a thin, swift and shining trickle. Angélique stared at it. The hours were passing, the night would soon be gone.

(Golon, Sergeanne. Angélique in Revolt. London: Pan Books, 1966, p. 363)

March 2021

In the fullness of the gifts which had made her a woman, she was reaching that extraordinary age at which for each and every woman, life, while continuing its headlong course, seems to grow lighter, to grow purer, and to be renewed in the apotheosis of a liberty of mind and soul, which has been hard won but is all the more precious for that, when the weight of the mistakes which were often no more than the apprenticeship to the harsh trade of living, becomes less irksome. It is permissible to leave behind along the way the burdens of the past, to forget what can be forgotten, to remember only the richness of that imperfect and difficult adventure of the full time of life.

(Golon, Sergeanne. The Temptation of Angélique. Book two. London: Pan Books, 1971, p. 136)

January - February 2021

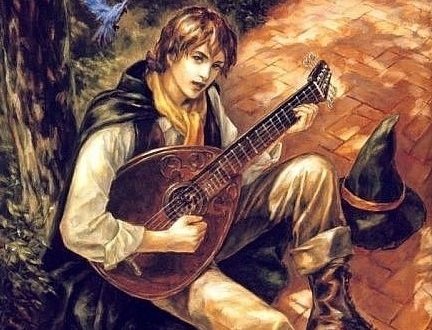

Marie-Agnès's convalescence proceeded satisfactorily at the Hôtel de Beautreillis. The young girl, however, remained ailing and in low spirits. She seemed to have forgotten her crystalline Iaughter which had enchanted the Court, and displayed only the demanding and impulsive side of her nature. In the beginning, she evinced no gratitude whatsoever for Angélique's kindness. But as her sister regained her strength, Angélique availed hersetf of the first opportunity to box her ears soundly. Thereafter Marie-Agnès declared that Angélique was the only woman with whom she could ever get on. With coaxing grace she would nestle close to her sister on winter evenings when they lingered by the fireside, playing a mandolin or doing some embroidery. They would exchange their impressions of the persons they both knew, and as each had a sharp tongue and a quick wit they sometimes laughed uproariously at their sallies.

(Golon, Sergeanne. Angélique. The Road to Versailles. London: Pan Books, 1966, p. 290)

November - December 2020

One evening Joffrey de Peyrac took Angélique's arm and led her down to the lakeside. The setting sun was reflected like rubies in the calm waters and the dry chilly air was pleasant. 'You seem worried, my love. I can see it in your face. Tell me what it's all about!' With a trace of embarrassment she told him of the fears that occasionally assailed her. First and foremost, she wondered whether ill-fortune or bad luck might not turn out to be too strong for them. (...) From under his doublet he drew the little golden cross he had taken from the neck of the dead Abenaki brave. 'Look at this. ... What do you see?' 'It's a cross,' she replied. 'As far as I'm concerned, what strikes me is the fact that it's gold. ... It was because I saw a large number of these little trinkets, crosses, and other emblems round the necks of the natives that I decided to explore this area. (...) The crosses spoke the truth, and I found it. As you see, I was guided by the cross. Wapassou is the richest of all the mines, but I have others scattered all over Maine. Now that I know that the Canadian Government has its eye on me, I must make haste to bring my work to fruition. ... I would have liked to install you more comfortably in Katarunk, but by coming here we have saved time. All we have so do is to get through this winter, and it will be tough. Here, our one and only enemy is nature. But it is from nature that I shall draw my strength. In the old days I possessed money without strength, and I need strength in order to have the right to live. I shall find it easier to acquire it in the New World than in the Old.'

(Golon, Sergeanne. The Countess Angélique. Ontario: Pan Books, 1968, p. 284-285)

September - October 2020

'Do you like jewellery?' He drew an iron coffer across the table towards him and threw back its heavy lid. 'Take a look.' He picked up a string of pearls, the most exquisite jewels with a milky iridescent glint and clasps of silver gilt. After he had held up the necklace for her to see, he laid it on the table and took another one: an enormous string of pearls, more golden this time, but all exactly of the same size and colour. There were so many of them that it seemed a miracle that anyone had ever been able to string them together. They could have gone ten times round her neck and still reached her knees. Angélique looked in perplexity at these wonders. Their appearance was an outrage to her humble fustian dress, her black cloth bodice laced up over a thick cotton blouse. Suddenly she felt ill at case in these plain clothes. 'Pearls, are they? ... I wore pearls just as beautiful as that when I was at the King's court,' she thought. 'No, not quite as beautiful as that,' she immediately corrected. Then all of a sudden she no longer felt ill at ease. 'It was a rare pleasure to possess such lovely things, but it was a weighty burden. Now I am free.'

(Golon, Sergeanne. Angélique in Love. London: Pan Books, 1969, p. 68)

July - August 2020

She had walked right round the castle and found herself at the base of the wall which she had so often climbed in the old days to steal a glance at the treasures in the enchanted room. (...) The window was open. Angélique bent forward. She guessed that the room was inhabited, for a small oil-lamp was shedding a golden glow, which only enhanced the glamour of the beautiful furniture and tapestries. She could see, shining like snowy crystals, the mother-of-pearl insets on the small ebony chest of drawers. Suddenly, as she was gazing at the tall damask bed, Angélique had the impression that the painting of the god and goddess had come to life. Two naked white bodies were clasped amid disarrayed sheets whose lace borders were dragging on the ground.

(Golon, Sergeanne. Angélique, the Marquise of the Angels. London: Pan Books, 1966, p. 84)

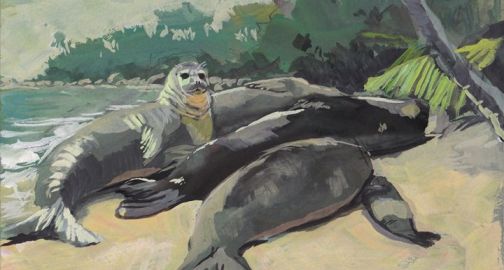

June 2020

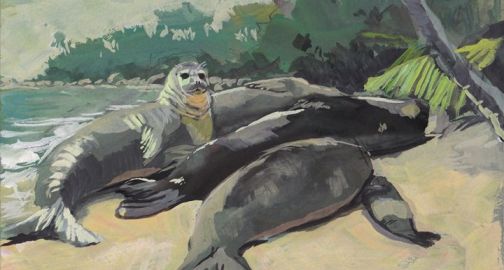

The light she saw was not the fatal decoy she had imagined, but only the brilliance of the long June night, so slow to die, as it stretched out over the earth its green, phosphorescent awning... A colony of sealions lay along the beach, and the big bulls, called the masters of the beaches, stood out here and there, dark monolithic creatures, gazing out towards the shimmering sea, watching heaven knows what, while the smaller and blacker glistening females lay coiled around them... (...) During the previous century a traveller had described the seals with some surprise: 'Their heads are like those of dogs, but without any ears, and their coats are the colour of the brown homespun worn by mendicant hermits, like the habit of our Minim Friars.' Angélique had read this when she was a child and had dreamed of sailing to America... and now, here she was, on this godforsaken American shore, a woman who had reached her middle years, no longer the dreamy, excitable child from the old château of Monteloup, and yet she felt as if little had changed within her. 'Our characters are formed in the cradle... We can only change by disowning ourselves...'

(Golon, Sergeanne. The Temptation of Angélique. Book two. London: Pan Books, 1971, p. 26-27)

May 2020

Her father saw her emerge skipping from one foot to another and clapping her hands to the rhythm of the ballads and rondos. Her burnished gold hair was bobbing on her shoulders. Perhaps on account of her short, tight dress, he suddenly realised how much she had grown during the last months. She, who had always been rather frail, now looked all of her twelve years; her shoulders had broadened, her breasts strained gently against the worn serge of her dress. Under the golden tan of her cheeks her full-bloodedness shone with a rosy glow, and her moist lips were half opened in a laugh which revealed her small perfect teeth. Like most of the young country girls, she had slipped a big bunch of mauve and yellow primroses into the opening of her bodice.

(Golon, Sergeanne. Angélique, the Marquise of the Angels. London: Pan Books, 1966, p. 46)

April 2020

Hortense received her sister and the lawyer with a frankly hostile expression. 'Splendid! Splendid!' she said. 'I noticed that from each one of your escapades you return in a more lamentable state. And always accompanied, of course.' 'Hortense, this is Maître Desgrez.' Hortense turned her back on the lawyer. (...) There was a ring at the door, and Barbe let in Gontran. The sight of him put the final spark to Hortense's anger, and she broke out into imprecations: 'What have I done to Our Lord to be burdened with such a brother and sister? Who could now believe that my family is really of ancient lineage? A sister who comes back dressed like a rag-picker! And a brother who, falling lower and lower, is reduced to becoming a rough labourer whom noblemen and burghers can treat with contempt and trounce with their sticks! ... They should have locked the whole lot of you up in the Bastille with that awful lame sorcerer!'

(Golon, Sergeanne. Angélique, the Marquise of the Angels. London: Pan Books, 1966, p. 392)

February - March 2020

She set off at a brisk walk, back to her daughter. Rain was falling. The puddles along the path reflected the whitish sky. A man on horseback overtook her and half turned round in his saddle. It was Maître Gabriel. 'Will you ride pillion with me, Dame Angélique?' A sudden weird feeling swept over her. She saw herself walking along a bumpy road under similar circumstances; a horseman turned towards her and his smile was the smile of Maître Gabriel. 'No,' she heard herself answer after a longish pause. 'I am only your servant-girl, Maître Gabriel. People would talk. ...' 'It's true that we are not on the outskirts of Paris here, on the Charenton road.' The veil was torn aside. La Polak was beside her. Her feet were frozen as they were now. (...) Twelve years had evaporated. The two scenes were side by side, twin situations. Totally forsaken as she had been, she had been momentarily comforted by the stranger's compassionate smile.

(Golon, Sergeanne. Angélique in Revolt. London: Pan Books, 1966, p. 251-252)

January 2020

Morning came soundlessly. The world, exhausted, scarce dared come to life again. In the rooms of the fort, the day dawned grey, for snow had piled up right across the windowpanes. But no sooner had they drawn the door open, not without some difficulty, than a glorious winter day, all pearly and gold, burst upon them. Nature was smiling in the brightness of a virginal beauty that was almost excessive, so pure and white was the snow, so satiny blue the sky, so golden the sun, and so perfect the soft lines of the trees looking like tall candles, motionless ghosts, turrets of clouds, with an occasional dome of branches bowed down like those of a tree in spring beneath a profusion of heavy, velvety blossom.

(Golon, Sergeanne. The Countess Angélique. Ontario: Pan Books, 1968, p. 401)

December 2019

'(...) Why have you suddenly become so abstracted?' 'I'm freezing.' The King looked astonished. 'Freezing?' 'The fire has gone out, Sire. It's the dead of winter, and it's two o'clock in the morning.' An amused surprise was discernible on the features of Louis XIV. (...) He peeled off his thick brown velvet coat and draped it about her shoulders. She sniffed its male smell mingled with the orrisroot perfume he loved and which characterised his prestige and the awe he inspired. It gave her an almost sensuous pleasure to pull the gold-braided lapels of the coat over her breast. The hand the King laid on her shoulder warmed her like the hand in her dream. She closed her eyes for a moment, then opened them again. The King was on his knees by the hearth, efficiently poking at the logs and fanning the embers till they sprang into a blaze.

(Golon, Sergeanne. Angélique and the King. London: Pan Books, 1968, p. 279-280)

November 2019

He had helped her to try on the dresses. They were all magnificent. She was, at that moment, wearing the purple dress with the rich, glowing texture. The velvet folds gave greater fullness to her figure, the chief characteristic of this rather heavy but sumptuous dress being its regal quality. Joffrey stepped behind her. Across her bosom and over her shoulders he placed a diamond necklace. Each stone was crowned with a small ruby. It was like a breastplate of incalculable worth. He stood there very erect, looking very dark beside the whiteness of her skin and the pale gold of her hair, and examined her critically in the mirror, and she was back once again reliving that day long ago when he had clasped his first gift about her slim seventeen-year-old neck. She quivered under the caress of his masterful hands. He was still the same, the Troubadour of Languedoc, with the same passionate flame burning in his eyes. 'Have we come back again to the beginning of our life together, after all these years?' she asked herself. Living with Joffrey de Peyrac was an adventure one could only come to know through him.

(Golon, Sergeanne. Angélique and the Ghosts. London: Pan Books, 1979, p. 319-320)

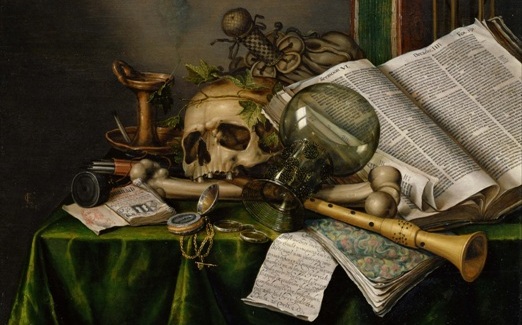

October 2019

A quarter of an hour later, Flipot was scampering towards the Pont-Neuf, whistling now and then to make himself known to marauders. Angélique knew that Big Matthieu had an almost miraculous remedy to stop bleeding. On occasions, when it was specially requested, he also had a way of making himself unobtrusive. ... He arrived at once and attended to the young patient with the energy and skill of long experience, while soliloquising as was his habit: 'Ah! little lady, why didn't you use the electuary of chastity which Big Matthieu sells on the Pont-Neuf? It is made of camphor, liquorice, vine-seed and waterlily seeds. Take two drams of it morning and evening, followed by a glass of whey in which you've dipped a piece of red-hot iron. ... Believe me, little lady, there's nothing better to suppress Venus's excessive ardours, which are paid for so dearly. ...' But poor Marie-Agnès was quite unable to hear these belated recommendations. With her diaphanous cheeks, mauvehued eyelids and the thin, drawn face amid the copious black hair, she looked like a sweet, lifeless wax figure.

(Golon, Sergeanne. Angélique. The Road to Versailles. London: Pan Books, 1966, p. 287)

September 2019

That morning had found them at the chapel of the hermit, a hoary Recollect in grey homespun, to attend the religious service. They sang the hymns with ill grace but in stentorian voices. 'Dreadful,' said Ville d'Avray as they came out. 'They nearly deafened me. Ah my dear, you will hear the singing in Quebec! The Cathedral choir and the Jesuits' choir...' 'You seem very sure you are going to see us in Quebec. As far as I am concerned, the project does not seem at all likely to come off. We are now in September, I don't know where my husband is... and in any case I cannot spend the winter so far from my little girl whom I have left in an isolated fort on the frontiers of Maine...' 'Bring her with you!' said Ville d'Avray as if it were the simplest of things to arrange. 'The Ursulines will teach her the alphabet and she can skate on the Saint Lawrence...' In spite of the attractions of the festivities that were being prepared and that had brought Acadians from far and wide, including a few English and Scots settlers, as well as the chiefs of neighbouring tribes, Angélique felt that she could not join in with a light heart.

(Golon, Sergeanne. Angélique and the Demon. London: Pan Books, 1975, p. 326-327)

August 2019

Although their progress was slowed up by having to ford a river and by the narrownes of the path, the trip still took under an hour. In fact it was nothing more than a short walk, and the children had set out gaily to stretch their legs a little. Some ruined huts came into sight, built about fifty years earlier by Champlain's unfortunate colonists. They had been abandoned, but some were still standing beneath the trees in a vast clearing that sloped gently down to a coral-red beach. But this shore was far from offering the same shelter they had seen a few miles away, for it was littered with rocks incessantly pounded by the raging sea. The children appeared, chasing each other in and out between the huts. 'Mama,' shouted Honorine, as she came rushing up, 'I've found our house. Come and see, it's the nicest house of all. There are roses everywhere. And Monsieur Cro has given it to us, for you and me, just for us.' (...) Angélique found herself standing in front of a wooden thatched house covered with full-blown sweet-smelling roses the colour of porcelain. 'Here's my house,' Honorine announced. And she ran round it twice, twittering like a swallow.

(Golon, Sergeanne. Angélique in Love. London: Pan Books, 1969, p. 344-345)

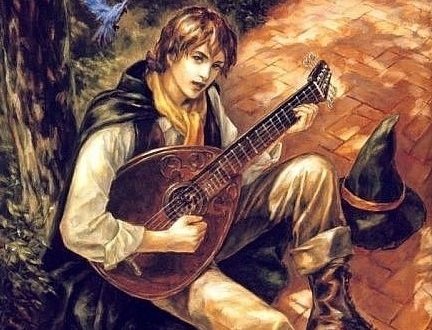

July 2019

'(...) Then Cantor got the idea he should go and look for him by sea.' 'Why by sea?' 'Because it's so vast,' he said with a sweep of his arm. He seemed to think of the sea as something he had no true notion of but which nonetheless was a gateway to realms where every wish came true. Angélique could understand. 'Cantor made up the song,' Florimond continued. 'I don't remember all the words, but it was very pretty. It was the story of our father. He used to say: "I will sing this song everywhere I go, and plenty of people will recognise him and tell me where he is."...' Angélique felt her throat tighten and her eyes grow moist. She could picture the two of them plotting the quest of the little troubadour for that legendary man. (...) '... Mother, do you think he has met my father?' Angélique stroked his hair without replying. She could not bring herself to tell him again that Cantor had paid with his life, like the Knights of the Holy Grail, for chasing a phantom. Poor little knight! Poor little troubadour! She could see his face, eyes and lips closed, floating in the transparent emerald depths of the bottomless seas, drifting like an image in a dream. '... by singing,' Florimond murmured, his thoughts wandering on in the same pattern. She had never known before what lay behind his frank eyes. The world of childhood, with its strange mingling of wisdom and nonsense, had long since passed beyond her ken. 'All children get foolish ideas,' she said to herself. 'The worst of it is, mine put them into effect.'

(Golon, Sergeanne. Angélique and the Sultan. London: Pan Books, 1968, p. 42-43)

June 2019

Then she laughed again, intoxicated by this June night, spellbound by its endless strident sounds. Louder even than the bagpipes, came the rhythmic call of the fifes and drums. Angélique leapt to her feet. 'Miss Pidgeon, Mrs MacGregor, Mrs Winslow and you, Dorothy and Janeton, come, come ... Let us go and dance the farandole with the Basques.' And she seized them by the hand, drawing them along with her as she ran down the slope. The Basques advanced one behind the other, bare footed and on tiptoe, capering and whirling as they went; they were prodigious dancers, full of grace and vigour, and the glow of the fires shone on their poppy-red berets. A tall supple fellow spun round and round in front of them, holding aloft a tambourine with copper jingles which he tapped with his nimble fingers. When Angélique and her companions entered the ring of firelight the men gave them a noisy welcome and made room for them at their sides. (...) The farandole went on weaving its sinuous way among the bonfires, the houses, the rocks and the trees. Every woman, old or young, grandmother, mother, girl or child must join in the dancing on Midsummer night.

(Golon, Sergeanne. The Temptation of Angélique. Book two. London: Pan Books, 1971, p. 51-52)

April - May 2019

Angélique, seated between the Archbishop and the man in red, and incapable of swallowing a morsel, saw an incalculable number of courses and dishes parading past. Potted partridges, fillets of duck, pomegranates in blood, fried quail, trout, rabbits, salad, lamb tripes,

foie gras. The sweets were innumerable - fried cream garnished with peach fritters, all kinds of jams, honey pastries, and pyramids of fruit as high as the little blackamoors who were carrying them. Wines of all types, from the darkest red to the clearest gold, followed one another. Angélique noticed at the side of her plate a kind of small golden pitchfork. Glancing around, she saw that most people used it to impale their meat and carry it to their mouths. She tried to imitate them, but after a few fruitless efforts preferred to revert to a spoon, which had been placed beside her when they saw that she did not know how to use the odd little instrument. This ridiculous incident added to her confusion.

(Golon, Sergeanne. Angélique, the Marquise of the Angels. London: Pan Books, 1966, p. 148-149)

February - March 2019

'(...) This evening, as I was studying the Scriptures, I took myself to task for not having treated you fairly. I should have given you some of your wages in advance.' 'You are not obliged to, Maître Gabriel. I know that a servant must give satisfaction for a month before receiving her salary.' 'But you arrived here with absolutely nothing. And it is written in the Bible: "Thou shalt not oppress an hired servant that is poor and needy, whether he be of thy brethren, or of the strangers that are in thy land within the gates; at his day thou shalt give him his hire, neither shall the sun go down upon it; for he is poor and setteth his heart upon it." So here is what I have decided to give you.' He handed her a purse that he had taken from amongst the folds of his clothes. 'Although it's a bit after sundown,' he added. A touch of humour occasionally belied his solemnity. Angélique thought that had he been born into another religion, in another city, he might well have become a witty epicure like the Chevalier de Méré.

(Golon, Sergeanne. Angélique in Revolt. London: Pan Books, 1966, p. 237)

December 2018 - January 2019

When, later that evening, the hunting horn was sounded, and Florimond and Cantor rang a peal on the cowbells, the children of the Silver Lake rushed over to the house, running, slipping, and stumbling over on the frozen snow, and stopped on the threshold, as dazzled and delighted as any other children the world over. 'Oh!' The room was a-glitter with a thousand lights and the table that occupied the centre of the room groaned beneath a pile of treasures and knick-knacks. It was hard to say which was best, the wonderful sight before them or the delicious smells of the fried black pudding and all the sweetmeats. The three tiny tots of the Silver Lake stood on the threshold, their eyes shining like stars in their faces red with the cold.

(Golon, Sergeanne. The Countess Angélique. Ontario: Pan Books, 1968, p. 409)

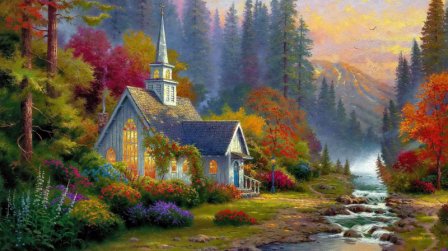

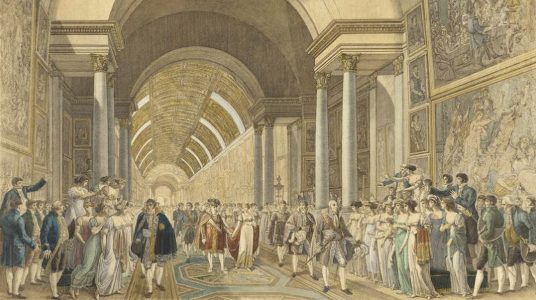

October - November 2018

With a wild look, she ran through the corridors of the Louvre. She was looking for Kouassi-Ba! She wanted to see the Grande Mademoiselle! . . . In vain, her anguished heart cried out for help. The figures she passed were deaf and blind, unsubstantial puppets from another world. Darkness fell, bringing with it an October storm that lashed the window-panes, beat down the flickering candle-flames, whistled under the doors, and stirred the draperies. Colonnades, stone-masks, the solemn shadows of giant staircases, gilt wainscots, bridges and galleries, tiled floors, pier-glasses, mouldings - Angélique roamed through the Louvre as through a gloomy forest, a fatal labyrinth.

(Golon, Sergeanne. Angélique, the Marquise of the Angels. London: Pan Books, 1966, p. 356)

August - September 2018

"Will-power is a magical and dangerous weapon," he remarked. Angélique looked at him with sudden anger. Every time he spoke like that he seemed to be reading he mind. "Do you mean it's better to let life and events overwhelm you, like a wounded dog at the mercy of the waves?" "Our destiny is not in our hands. What is written is written." "You mean no one can change his fate?" "Yes, one can," he said soberly. "Every human being prossesses a boundless potentiality for counteracting fate. That is why I said will-power is a magical and dangerous weapon. It is the force of nature. It is dangerous in that one often pays too dearly for the results one achieves. That is why Christians who use their wills for every advantage and every wicked purpose are always at war with their destiny and bring down upon their heads the woes of which they so continually complain." Angélique shook her head. "I cannot understand you, Osman Bey. We belong to two different worlds."

(Golon, Sergeanne. Angélique and the Sultan. London: Pan Books, 1968, p. 247)

June - July 2018

"It was at Plessis. I was sixteen and my father had just bought me a regiment. We were in the country to recruit it. At a party I met a girl the same age as I, but in my jaundiced eyes only a child. She was wearing a gray dress with blue bows on its bodice. I was ashamed when they told me she was my cousin. But when I took her hand to dance I felt it tremble in mine, and then I experienced a new and wonderful sensation. Up until then it was I who had trembled before the imperious desire of mature women or the teasing flirtatiousness of the young minxes at Court. This girl baffled me. The look of admiration in her eyes was balm to my soul, an intoxicating draught. Suddenly I realized I was a man, not some plaything; a master, not a servant. (...)"

(Golon, Sergeanne. Angélique and the King. London: Pan Books, 1968, p. 193)

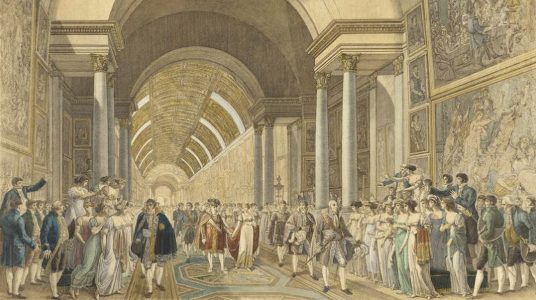

April - May 2018

One day Angélique asked Mademoiselle de Parajonc to accompany her to the Tuileries. The latter was her constant companion. (...) The Tuileries, according to Mademoiselle de Parajonc, were 'the lists of high society', and the Cours-la-Reine the 'empire of amorous glances'. One frequented the Tuileries to await the proper hour for the Cours, and one met there again in the evening after the Cours, alternating the drive in the carriage with promenades on foot. The wooded groves of the park were favourable to poets and lovers. Abbés prepared their sermons there, lawyers their speeches. All persons of rank came there for rendezvous, and one sometimes met the King or the Queen, or Monseigneur the Dauphin with his governess.

(Golon, Sergeanne. Angélique. The Road to Versailles. London: Pan Books, 1966, p. 258)

March 2018

"Imagine, the entire Plessis clan - Marquis, Marquise, son, pages, valets, dogs, have moved into the château. They have an illustrious guest, the Prince de Condé and all his Court. I ran into the lot of them and was quite ill at ease. But my cousin acted very amiably. He called me, inquired after you, and do you know what he asked me? To take Angélique to him, to replace one of the maids-of-honour. The Marquise had to leave behind in Paris practically all the girls who dress her hair, amuse her and play the lute. The Prince de Condé's coming has got her in a flutter. She says she needs a few graceful little maids-in-waiting to help her." "And why not me?" exclaimed Hortense, scandalised. "Because she said 'graceful'," was her father's unequivocal reply.

(Golon, Sergeanne. Angélique, the Marquise of the Angels. London: Pan Books, 1966, p. 76)

February 2018

"The soft ones are whining ninnies. The ambitious have to be beaten down lest they devour me. But you ... you were born to be a

sultana-bachi, as that dark prince said who wished to carry you avay with him. The one who can dominate a king. I accept the title. I bow. I love you in a hundred different ways - for your weakness, for your sadness I would so like to dispel, for your splendour I would so like to possess, for your intelligence which confounds me but which I need as much as I need precious things of gold and marble about me, almost too beautiful in their perfection than one should have near one, as a token of wealth and strenght. You have given me what I lacked - confidence."

(Golon, Sergeanne. Angélique and the King. London: Pan Books, 1968, p. 339)

January 2018

It was the day after Epiphany and all Paris had sore throats from yelling 'The King Drinks', or was sick from overeating the huge Twelfth Night cakes and drinking goblet after goblet of wine. There had been much feasting at the Hôtel de Beautreillis. Florimond was the 'King', wearing a gold paper crown and lifting his glass to all the cheers. Today everyone was sleepy and yawning. A fine day to bring a child into the world! In her impatience Angélique kept asking about housekeeping details. Had the left-overs been given to the poor? Yes, four baskets had been taken to the cripples' pole that very morning. Two buckets had been taken to the Blue Children, the orphans of the Temple district, and to the Red Children, the orphans of the Hôtel-Dieu.

(Golon, Sergeanne. Angélique and the King. London: Pan Books, 1968, p. 132)

December 2017

A few days before Christmas snow began to fall. The city donned festive garb. In the churches, crèches were being set up. The banners of the brotherhoods led long, chanting processions through the narrow streets filled with snow and slush. In accordance with custom, the Augustinian friars of the Hôtel-Dieu hospital began to produce thousands of fritters, sprinkled with lemon-juice, which children sold throughout Paris. One was allowed to break the fast only with these fritters. The money derived from their sale would help to provide a Christmas celebration for the needy and sick. At this time Angélique, caught up in the lugubrious complications of the dreadful trial, hardly realised that she was Iiving through the blessed hours of Christmas and the first days of the New Year.

(Golon, Sergeanne. Angélique, the Marquise of the Angels. London: Pan Books, 1966, p. 411-412)

November 2017

They had been granted the respite predicted by the Canadians. The end of October and the beginning of November brought a sudden miraculous dry spell and delightful warmth. Only the nights were cold, and sometimes in the mornings the mountains stood out blue beneath a powdering of frost. (...) Angélique fought with the birds for the last red berries of the mountain ash and some black elderberries. She would use these to treat fevers, bronchitis, aches, and pains, sore kidneys. She sent Elvire and the children off to pick anything edible they could still find on the bushes, in the thickets, or on the open ground, any kind of berry, bilberries, whortleberries, little apples or stunted wild pears. (...) Savary had taught Angélique, during the course of her travels, to value the merest scrap of fruit peel. There was little enough of it here and it would be many a long months before they saw any more ripen. But the dried berries would be a help. Next the children picked caraway seeds, mushrooms from moist hollows, hazelnuts, and mast for the pig.

(Golon, Sergeanne. The Countess Angélique. Ontario: Pan Books, 1968, p. 271-272)

October 2017

On coming in he sensed that she was asleep. There were traces of her now familiar feminine scent in the half darkness. Seeing her garments strewn here and there he smiled. What had become of the puritanical, stand-offish little Huguenot woman from La Rochelle, dressed as a servant, whom the Rescator, sailing to America, had brought to his luxurious cabin that long-ago day to attempt to tame her? What, indeed, had become of the woman pioneer who throughout that long, terrible winter in the Upper Kennebec had remained at his side, assisting him with never-failing courage? He picked up a scrap of lace, a bodice whose silk still retained the shape of her full curves. After being a nameless servant, then the helpmate of an explorer of the New World, here at last was his Angélique turning into Madame de Peyrac, Countess of Toulouse, once again. 'May God so will it!' he murmured to himself, casting an ardent glance in the direction of the alcove where the sheen of her hair was faintly visible.

(Golon, Sergeanne. Angélique and the Ghosts. London: Pan Books, 1979, p. 65)

September 2017

September came, cold and rainy. "Here comes Homicide," Black-Bread growled, taking refuge by the fire, with dripping rags. The damp wood hissed in the hearth. For once, the burghers and wealthy traders of Paris did not wait for All Saints to unpack their winter clothes and get a blood-letting, according to the traditions which recommended this surrender to the surgeon's lancet four times a year, at the change of seasons. But the noblemen and the beggars had other topics to worry them than talk of the rain and the cold. All the high personages at Court and in finance were stunned by the arrest of the exceedingly rich Controller-General of Finance, Monsieur Fouquet.

(Golon, Sergeanne. Angélique. The Road to Versailles. London: Pan Books, 1966, p. 110-111)

August 2017

This time it was his smile that cut short what she was saying. It was a smile that revealed a row of still splendid shining teeth. It was certainly the smile of the last of the troubadours, but a veil of melancholy and disenchantment hung over it. 'Fifteen years, Madame! Just consider it. Let us not be stupid and unworthy enough to delude ourselves. Since then we have both of us had other experiences, and other loves.' It was then that the truth she had been refusing to face pierced her like the ice-cold point of a dagger. She had found him, but he no longer loved her. All her life she had dreamt of him coming towards her with open arms. Now she realized that these dreams, had been nothing but childish imaginings, like most women's dreams. Life is carved out of a rock tougher than the soft and easy wax of dreams. It is shaped by great cutting blows, blows that jar and hurt.

(Golon, Sergeanne. Angélique in Love. London: Pan Books, 1969, p. 83)

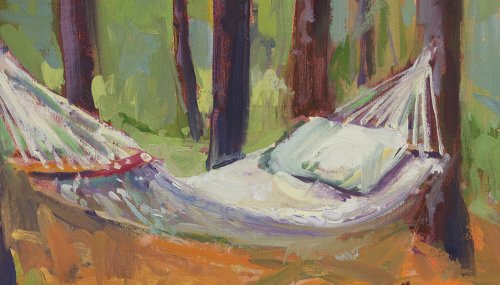

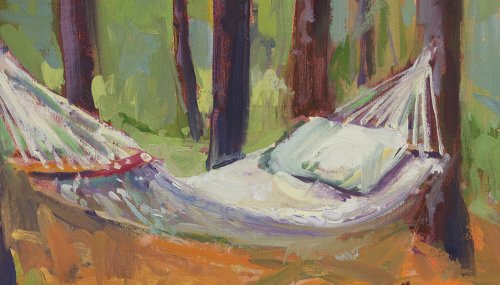

July 2017

Angélique found Monsieur de Ville d'Avray relaxing in a huge cotton hammock suspended from two beams, while his young son played on the floor beside him with some pieces of wood. 'This is an authentic Caribbean hammock,' the Governor explained. 'Extremely comfortable! You have to know how to lie in it - diagonally from corner to corner - and then it's marvellously restful. I bought it for a few twists of tobacco from a Caribbean slave who was passing through with his master, deserter from some pirate ship.'

(Golon, Sergeanne. Angélique and the Demon. London: Pan Books, 1975, p. 315)

June 2017

The clergyman thanked him and asked for permission to withdraw in order to 'have a wash'. 'Wasn't that downpour enough for him?' wondered Angélique. 'Odd people, those Huguenots! It is rightly said that they aren't like other people. I'll ask Guillaume if he, too, has a wash at odd moments. Must be part of their rites. That's why they so often look guilty, or else are touchy like Lützen. Their skin must be quite thin with scrubbing, it must ache. ... Like young Philippe, who feels an urge to wash at all times! This constant concern with himself will probably lead him to heresy, too. Maybe they'll burn him and it'll serve him right!'

(Golon, Sergeanne. Angélique, the Marquise of the Angels. London: Pan Books, 1966, p. 70)

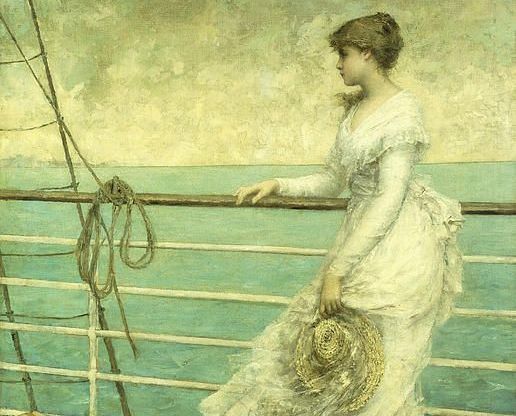

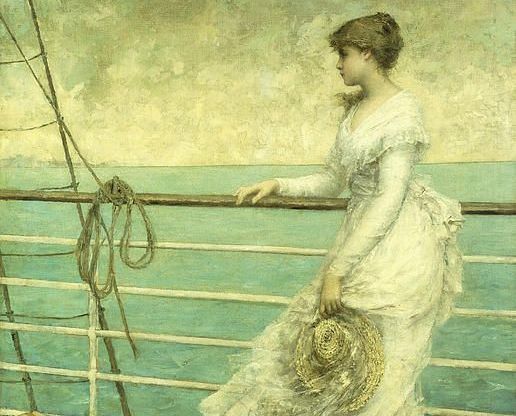

May 2017

Never is a woman more vulnerable than when she feels the need for consolation in her beloved's absence. Men should be aware of this; husbands should know it. (...) Dreamily, as the ship rose and fell, she let her thoughts wander through the moonlight, and saw in her mind's eye a procession of all the men she had ever known, all so different, among whom suddenly and without her knowing why, she caught sight of the frank, open face of Count Lomenie-Chambord and the distant, noble figure, hieratic yet forbearing of the Abbot of Nieul.

(Golon, Sergeanne. The Temptation of Angélique. Book one. London: Pan Books, 1971, p. 183-184)

April 2017

Angélique and Abigail stood side by side in the tiny garden surrounded by tall clumps of flowers and grass. The garden, laid out around the Bernes' house and fenced in the New England manner, was one such as every settler's wife needed to help keep her family in good health in these areas where an apothecary might be found only at a considerable distance. Added to this there were a few vegetables - lettuces, leeks, radishes, carrots - herbs for seasoning, and masses of flowers for sheer pleasure. With her foot Abigail pushed back a round velvety leaf that had strayed out of its bed.

(Golon, Sergeanne. Angélique and the Demon. London: Pan Books, 1975, p. 72)

March 2017

Louis XIV entertained the ladies of the Court at his table. One evening at dinner his glance fell on Angélique sitting not far from him. His recent victories, not to mention the more personal one over Madame de Montespan, and the exhilaration of triumph, had somewhat dimmed his usually keen powers of observation. He thought he was seeing her for the first time during the campaign and asked her pleasantly: "So you have left the capital? What were they saying in Paris when you set out?" Angélique looked at him coolly. "Sire, they were saying evening prayers." "I meant, what was new?" "Green peas, Sire."

(Golon, Sergeanne. Angélique and the King. London: Pan Books, 1968, p. 165)

February 2017

She took him into the next room where she had had a table set with him in mind. Gold candlesticks were lit at either end. On a golden platter lay a huge roast turkey stuffed with chestnuts and garnished with baked apples. Beside it were covered dishes of hot and cold vegetables, an eel stew, salads, and a golden bowl full of fruit. To honor the poor fellow after his sojourn in the forest, Angélique had had the table laid with some of her gold service, of which she was very proud. Besides the platter, the candlesticks and the bowl, she had set out two priceless antique goblets and ewers.

(Golon, Sergeanne. Angélique and the King. London: Pan Books, 1968, p. 320)

January 2017

Amongst the regiments the King sent to Poitou in 1673 was the 1st Auvergne regiment commanded by Monsieur de Riom, and five of the most famous companies of the Ardennes. The King had heard enough about the soldiers' superstitious fears of ambushes in the Poitou forests. The men he was sending there now were sons of Auvergne and the Ardennes, picked from among forest dwellers, and they had all been accustomed since their earliest youth to the haunted darkness of the woods, to wild boars, wolves and cliffs, and were used to finding their way through apparently trackless wastes. They were all the sons of cobblers, woodcutters or charcoal-burners. (...) The King had said: 'By the spring.' Winter would not call a halt to the war.

(Golon, Sergeanne. Angélique in Revolt. London: Pan Books, 1966, p. 180)

December 2016

Angélique looked almost unreal in this dress of the dreams. Her amber-colored complexion, gently powdered, shimmered by a way that it seemed as if she was lit from within. (...) Delphine, a young chambermaid, has called Henriette and Yolande and even she asked for assistance the tailor and Kouassi-Ba because it was no easy matter to dress this cloak. The cloak was made out of white fur, lined with fine wool and white satin. It had a wide hood, embroidered with gold and silver threads at the reverse. One had to beware that the cloak would not drag on the ground because the deck boards were not always the cleanest.

(Golon, Anne - Golon, Serge. Angélique à Québec. A translation from the French language)

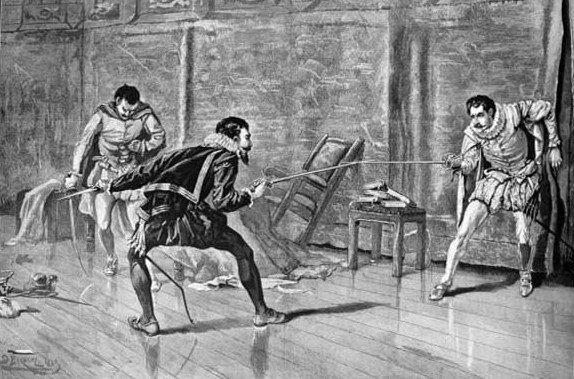

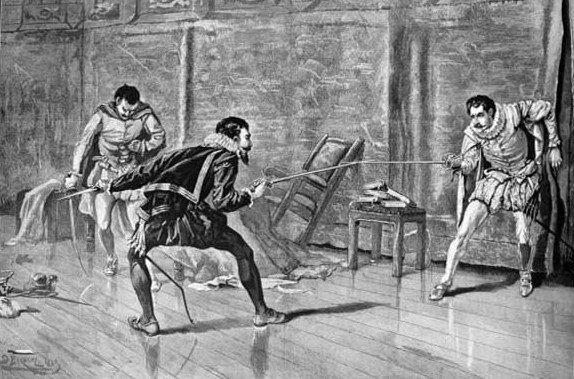

November 2016

Florimond collapsed on to his bed again, his eyes shining. 'Now, a sword, that's the weapon of a gentleman. Here in this land of clodhoppers, no one knows what a sword is any more. They fight with tomahawks and axes like the Indians, or with muskets like mercenaries. We really must remember the sword. It's the shaft of noble souls! Oh to be a cuckold one day and to be able to have a good duel.'

(Golon, Sergeanne. The Countess Angélique. Ontario: Pan Books, 1968, p. 405)

October 2016

Suddenly the massed baying of the hounds broke forth again. A brown shape leaped from the skirt of the woods. It was the stag, a young one with scarcely a prong on its antlers. The reeds on the marshy edge of the stream shook as it galloped past. The pack of hounds descended on the trail of the stag like a torrent of red and white. Then a horse emerged from the coppice carrying a huntress in a scarlet habit. Almost at the same moment the riders broke into the open from all directions and dashed down the grassy slope. In an instant the peacefull rustic glade had been invaded by the wild rout joining their cries to the frenzied baying of the hounds and the whinnying of the horses, the shouts of the huntsmen and the glorious fanfare of the horns sounding the 'View Halloo'.

(Golon, Sergeanne. Angélique and the King. London: Pan Books, 1968, p. 34-35)

September 2016

Angélique still wondered whether he really knew where he was going or whether it was mere chance that kept bringing them through safely. They ought to have been lost and have perished a hundred times over, but the fact remained that no one had perished. And for three weeks now, those who made up the little caravan that had left Gouldsboro during the last days of September, had bowed to their destiny, carried along and intoxicated by the forest through which they were journeying, like pebbles swept along in the flood of a torrent, their complexions brown and roughened at the angles, their eyes faded by the brilliant light, the dazzling blues, the blue of the sky seen through the coloured kaleidoscope of the leaves, and the folds of their garments redolent with the scent of wood fires and autumn, resin and raspberry. In the autumnal heat the mist that hung over the lakes would evaporate in the early hours of the morning, leaving the surface of the water dazzling and limpid, and the undergrowth so dry that it could be heard crackling at a considerable distance.

(Golon, Sergeanne. The Countess Angélique. Ontario: Pan Books, 1968, p. 13-14)

July - August 2016

When she reached the Quai de la Tournelle, the scent of fresh hay was wafted to her - the first hay of spring. The barges were moored in a long line with their light and fragrant cargo. In the Parisian dawn they exhaled a breath of warm incense, the aroma of a thousand dried flowers, the promise of lovely days to come. (...) She waded into the water and hoisted herself on to the prow of a barge. She delved voluptuously into the hay. Under the canvas cover the smell was even more intoxicating: moist, hot and charged with thunder like a summer day. Where could this hay have come from? From some silent, rich, fertile countryside, under a warm sun. This hay brought with it the quiet of vast, wind-dried horizons, of lofty skies filled with light.

(Golon, Sergeanne. Angélique. The Road to Versailles. London: Pan Books, 1966, p. 74-75)

May - June 2016

Whenever she set off to look for plants rather than to gather them, Angélique would go with Honorine and no one else. Now that the winter was over, Honorine had stopped being a child like the others, concerned only with fires and food and getting up to mischief, and once again she had become her mother's companion. There was a strange depth of understanding between them when it came to firearms or flowers. Honorine had stamina. She followed Angélique wherever she went, often covering about twice as much ground because of the way she ran hither and thither, looking at everything. To make quite sure she would not lose her in the wild woods, Angélique tied a little bell round her wrist, so that wherever she went, its happy sound revealed her position.

(Golon, Sergeanne. The Countess Angélique. Ontario: Pan Books, 1968, p. 537-538)

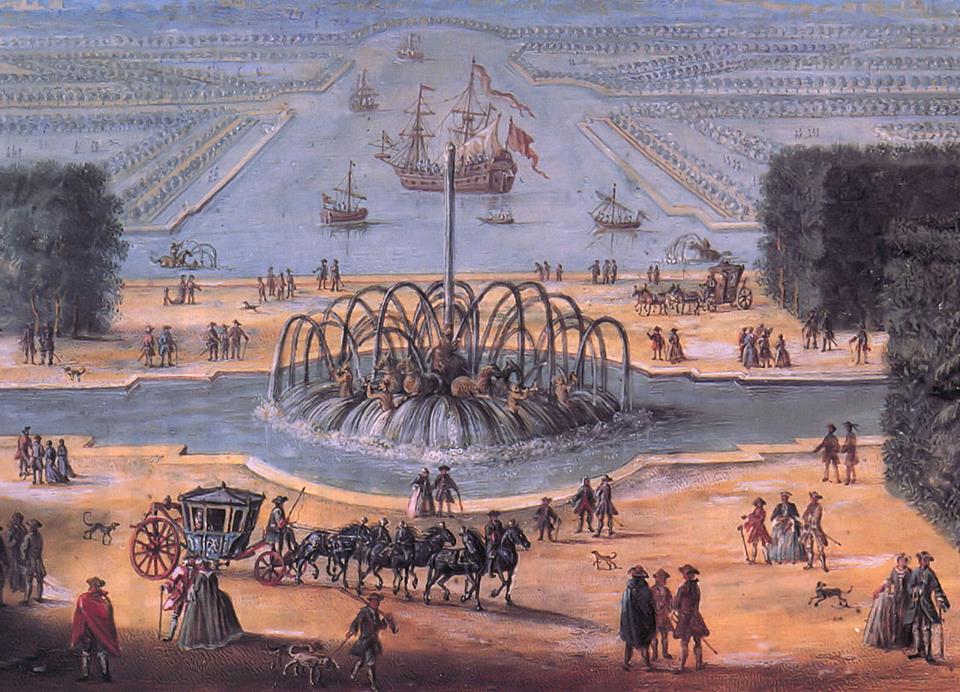

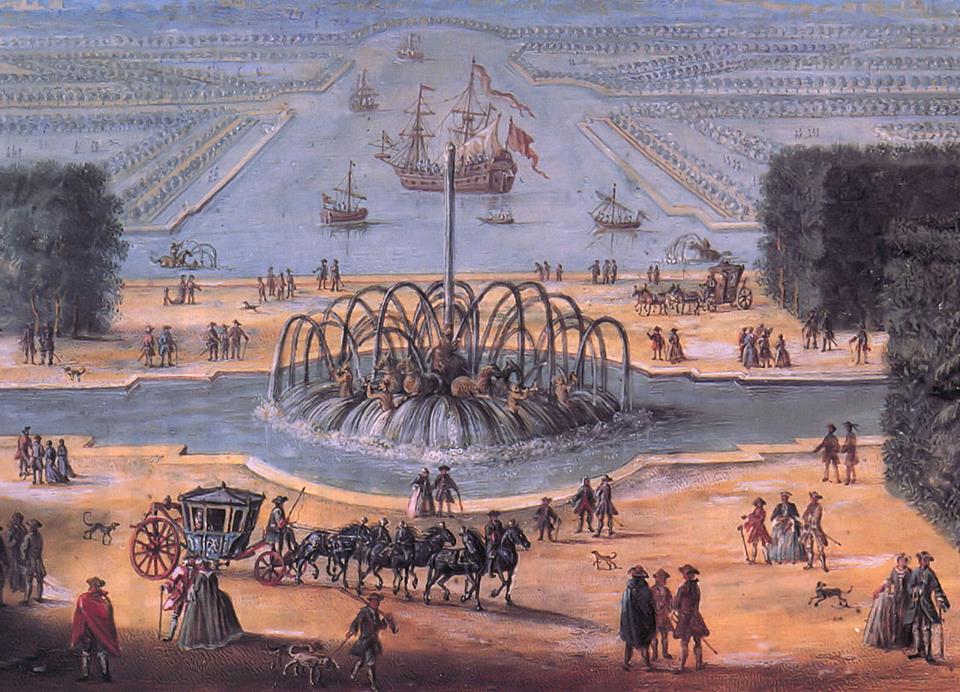

April 2016

Versailles was bathed in light. The warmth and springtime glow of an April day wrapped the palace in that rosy-golden vapour that belongs only to lands which know the joy of

dolce far niente. "How lovely Versailles is!" Angélique said to herself in a rapture of enthusiasm. Her spirits had revived; her anguish of soul was gone. At Versailles one had to believe in the mercy of God and in that of the King who had built this marvel. (...) Angélique sat on the edge of a large scallop-shell of jasper. Around her, graceful sea-nymphs held dripping, candelabra aloft, whose six branches imitating seaweed spouted jets of iridescent water. Hundreds of birds fluttered among the rosy mists of the vaulted roof, giving the grotto the sound of a grove.

(Golon, Sergeanne. Angélique and the King. London: Pan Books, 1968, p. 332)

March 2016

Angélique broke out in a cold sweat. It was nearly night. Behind the bars of the tiny window a reddish glow showed that it was evening. Angélique hammered on the cellar door, but nobody came, no one answered her call. She went back to the loophole and clutched at the bars. The opening was at ground level. A dull roar told her that she could not be very far from the sea. She called again, but in vain. Night was coming on, caring nothing for the prisoners walled up here alive, who could hope for nothing from their fellow men until the morning. Her mind became blank and empty for a while, and she must have rushed round and round shrieking like a soul in torment. A faint sound outside made her pull herself together. It was the sound of footsteps. Angélique went back to the cold rusty bars that covered the window. She clung there as the footsteps came nearer. Two shoes appeared at the other end of the little opening. "For the love of heaven, please stop, whoever you are going by. Listen to me," shouted Angélique. The shoes stopped. "For the love of God," she repeated fervently. "Listen to my plea." Nobody spoke, but the shoes remained motionless.

(Golon, Sergeanne. Angélique in Revolt. London: Pan Books, 1966, p. 211)

February 2016

After a short rest they set off again. They spoke little, conserving their strength for the almost superhuman efforts of the long walk, their feet clad in snowshoes made of rope, which were clumsy and impeded every step, and not adequate to keep them permanently on the surface of the soft, powdery snow. Each time a foot sank beneath the surface crust they had to lift it out by raising their knee, and, taking a further step, feel the snow give again under their weight. Florimond kept muttering about it, saying that someone ought to invent another way of walking on snow. (...) Florimond‘s muscles ached. He had thought himself young and strong, but now he realized how feeble his arms were when, in a space of twenty minutes, he was obliged to make the same muscular effort ten times to haul himself up out of a snowdrift by clutching the branches of a fir-tree.

(Golon, Sergeanne. The Countess Angélique. Ontario: Pan Books, 1968, p. 376-377)

January 2016

Kouassi-Ba went the rounds like one of the three kings, and with his black hand distributed a gold bar to each of the men. (...) Old Eloi lifted his and waved it in the air. "You have made a mistake, Monsieur le Comte. I am not one of your men. I just happened to come along and stayed. You don't owe me anything." "You are the labourer of the eleventh hour, you old pirate," Joffrey de Peyrac replied. "Do you know your Bible? Yes you do. Well then, think of what it says and hang on to what people offer you. You can get yourself a new canoe and enough goods to barter for two years, so you can come back with all the furs in the west. All your rivals will choke with jealousy...."

(Golon, Sergeanne. The Countess Angélique. Ontario: Pan Books, 1968, p. 419 and 420)

December 2015

Madame de La Vaudière triumphed. "That's exactly what I thought! Mr. de Peyrac is with the Jesuits." (...) It seemed Mrs. de la Vaudière is familiar with this place, and completely fearless. She was not impressed by the tiled porch, like Angélique. There were only some chairs, a large crucifix on the wall and a holy water stoup right of the door. Bérengère-Aimée dipped the tips of her fingers into it, with a mixture of informality and humility, which had to be regarded as a masterpiece of feminine grace and hypocrisy. She had an undeniable charm, and concurrently a cheery and pious daring, that is shown by some angels; by those who are surrounding the throne of the Almighty, and whose only job is just bringing somewhat of roguish touch there.

(Golon, Anne - Golon, Serge. Angélique in Québec. A translation from the Slovak language)

November 2015

They all felt equally reassured and excited by this fairy-tale stories, the same way how flourished in them the crystal clear diamond-hard soul of provinces. In silence, they were aware of the bliss of this thick protective wall around them, the true valour of the old building, which loomed like a black rocky island in the darkness, between the two original elements of creation, the water of the marshes in the former sea bay, from where the brackish depths of the ocean have withdrawn, and the gentle ruffling of the huge Celtic Forest, which covered the headlands at the end of the world.

(Golon, Anne. Angélique l’Intégrale: Die junge Marquise. A translation from the German language)

October 2015

She had lost none of her zest for living. This was a constant wonder to her, and she secretly thanked God that her trials had not broken her spirit. She still had the enthusiasm of a child. She had seen far more of life than most young women of her age, yet had been less disillusioned by the world. And like a child she could still get a wondrous excitement out of little things. If you've never known what it is to be hungry, how can you savour the taste of a piece of warm fresh bread? And once you've walked barefoot over the cobblestones of Paris only at last to own pearls like these, how can you doubt that you're the happiest woman in the whole wide world?

(Golon, Sergeanne. Angélique and the King. London: Pan Books, 1968, p. 14-15)

September 2015

Then, late in the afternoon, he revealed to her an almost invisible spring in the heart of a little clearing: the water gushed from it and disappeared almost immediately without a tremor, absorbed by the spongy ground, a silent, uninterrupted offering that came from the earth like an everlastingly sweet sorrow, a spring with a flavour of verdure. It brought the taste of leaves to one's tongue, spring was born again, in the mingled flavours of watercress, sage, and mint. The charm of this spring made Angélique lose all sense of time. (...) The white woman, he (Mopuntook) explained, was naturally enough, like all other women, somewhat obstinate, and a trifle inclined to suggest that a man did not know what he was about, but she did know about spring water and could distinguish different varieties by their taste. This was a great gift, a blessed gift.

(Golon, Sergeanne. The Countess Angélique. Ontario: Pan Books, 1968, p. 277)

July - August 2015

She went back up the narrow staircase, then another, and another, until finally she found herself on a terraced rooftop with the whole starry vault of the sky spread out above her. A silvery light tinted the cool mist rising from the sea into a bluish vapour that enveloped everything, even the dome of the nearby mosque. Its minaret seemed almost transparent in the rays of the moon, and it made her slightly dizzy as it seemed to sway in the shifting light.

(Golon, Sergeanne. Angélique and the Sultan. London: Pan Books, 1968, p. 239-240)

June 2015

"And I find, for my part, that you are all rather touchy in your family!" retorted Angélique, whose anger was getting the better of her terror. "When you are being fêted or made much of, you take offence because the one who receives you seems richer than you are! When you're being offered gifts, it's insolence! When someone doesn't bow to you deeply enough, it's another! When one doesn't live like a beggar, stretching out one's hand till the State is ruined, the way your farmyard of lordlings does, it's considered rank arrogance! When one pays taxes cash down to the last farthing, it's a provocation! ...A gang of petty pilferers, that's what you are, you, your brother, your mother, and all your treacherous cousins: Condé, Montpensier, Soissons, Guise, Lorraine, Vendôme...."

(Golon, Sergeanne. Angélique, the Marquise of the Angels. London: Pan Books, 1966, p. 362)

April - May 2015

The porter shook his head. Holy Week was about to begin, and the monastery was already in retreat. It was true that a more than usually heavy silence hung over the Abbey. These consecrated men were drawing together for the terrible pilgrimage of the days before Easter, and the woman had to withdraw. (...)

As bare two weeks before at this very place she had stumbled through the snow hardly able to breathe in the biting cold, and she felt in her flesh all the harshness of the barren winter. Today the valley was carpeted with green velvet, the stream that she had crossed, then sleeping beneath the ice, was now bounding along with all the grace and vigour of a young goat, and there were violets along the fringe of the wood. The cuckoo was calling his promise of warm days to come, of budding blossoms, of the coming of spring.

Angélique's eyes grew dim with tears as she looked at these marvels. Nature and life have their pleasant surprise too. Out of an exceptionally long and hard winter, grass and flowers were springing ten times more abundant than usual...

(Golon, Sergeanne. Angélique in Revolt. London: Pan Books, 1966, p. 207-208)

March 2015

The last threshold to cross in order to bask at last in the light of the Sun King – the marriage with Philippe – was crumbling. For that matter, she had always known that it would be too difficult and that she would not have strength enough. She was worn out, used up.... She was but a chocolate-manufacturer and would not be able to maintain herself much longer on the level of the nobility, which would never welcome her. She was being received, but not welcomed.... Versailles!.... Versailles! The glamour of the Court, the radiance of the Sun King! Philippe! Beautiful, unattainable god Mars!... She would drop back to the level of a

petite bourgeoise. And her children would never be gentlemen....

Absorbed in her thoughts, she did not realise that time was passing. The fire was dying in the hearth, the candle smoked.

(Golon, Sergeanne. Angélique, the Road to Versailles. London: Pan Books, 1966, p. 298-299)

February 2015

"My lambs," said Monsieur Vincent, "my little children of God, you have tried to taste the green fruit of love. That's why your teeth are on edge and your hearts full of sadness.

Let the sun of life ripen what has always been destined to blossom and mature. You must not stray in your quest of love, for if you do you may never find it.

What crueller punishment is there for impatience and weakness than to be condemned for ever to bite only into sour, savourless fruit?" (...)

Angélique did not look back until she had reached the convent gate. A great peace had settled within her. But her shoulder still felt the imprint of a warm, old hand.

(Golon, Sergeanne. Angélique, the Marquise of the Angels. London: Pan Books, 1966, p. 109)

January 2015

"What do you think of a storm like that, off Nova Scotia? It's magnificent, isn't it? Not like those paltry little squalls in the Mediterranean. Fortunately the world is bigger than that and not everyone in it behaves shabbily."

He was laughing. Angélique felt so indignant that she managed to get to her feet in spite of the fact that her skirt, weighted down with water, felt like lead.

"You're laughing," she shouted furiously. "Storms make you laugh, Joffrey de Peyrac... even torture makes you laugh. You sang when they were going to execute you in the square in front of Notre-Dame.

What do you care if I'm in tears? What does it matter to you if I am frightened of storms... even in the Mediterranean... without you..."

(Golon, Sergeanne. Angélique in Love. London: Pan Books, 1969, p. 244)

December 2014

A lone man was drifting in icy wasteland. The weeks of Advent Lent started. Christmas is definitely approaching. Christmas! Christmas!

While the bells chime and the breath of life escapes from all the chimneys as an incense burner, while the scent feasts blends with incense and lighted candles, amount to the frozen sky, to remind the Creator that humans are there, left in this inhuman desert, a man, bound by the vow of obedience, departs the save haven. Black Robe leaves at heavy footsteps of his racquet his circle of loving friends, their love, and the holy of holies of his works and his deeds.

The icy desert itself replaced all flames of life inside of him.

(Golon, Anne - Golon, Serge. Angélique à Québec/Angélique in Quebec. Translation from French and German language.)

November 2014

Anchored in the marina among the moving shallops and beside two small English warships, a Neapolitan felucca and a Biscay galley, the great vessel was swaying like a butterfly balancing on a blade of grass. It was a miniature frigate, equipped with small bronze cannons, on each of which shone the golden cock surrounded with fleur-de-lis, garlands, shells and sea gods. The ropes were of apricot and crimson silk, the hangings of brocade fringed with gold and silver. From the masts and spars, which were painted red and blue, floated pennons in a gay symphony of colors, and everywhere the arms and emblems of the King sparkled in gold.

Louis XIV was rendering this jewel of a ship the homage of his Court. One foot on the gilded gangplank, he turned toward his ladies. Who would be chosen to lead the procession from the meadows of Trianon? In his suit of peacock blue, the King looked as radiant as the cloudless day. He smiled and extended his hand to Angélique. Before the eyes of the entire Court she ascended the gangplank and settled herself under the brocaded canopy. The King sat beside her.

(Golon, Sergeanne. Angélique and the King. London: Pan Major, 1963, p. 408)

October 2014

Good lord, couldn't there be some place on this wide earth where a Breteuil had no right to scorn a Colin Paturel, or a Colin Paturel would not feel humiliated by his love for a noble lady of the Court...?

A new world where those possessed of kindness and good will, courage and intelligence, would be in command, and where those who lacked those qualities would always be inferior.

Couldn't she find some virgin land where men of good will would be welcomed? Oh Lord... where?

(Golon, Sergeanne. Angélique and the Sultan. London: Pan Books, 1963, p. 415)

September 2014

"It seems the Infanta still wears a hoop skirt with iron hoops of such dimensions that she has to go through a door sideways."

"Her corset is so tight that she seems to have no breasts at all, and yet she is supposed to have pretty ones," added Madame de Motteville, making the laces puff out over her own meagre bust. Joffrey de Peyrac looked down at her with a caustic eye. "The tailors of Madrid must truly be inexperienced thus to spoil what is beautiful, when our Paris tailors are so clever at making the most of what has ceased to be so."

(Golon, Sergeanne. Angélique, the Marquise of the Angels. London: Pan Major, 1961, p. 264)

July - August 2014

She was in the seventh month of pregnancy, her fifth in six years. She was only twenty-three years old. Behind her already was the greatest love affair any woman could hope for, before her a long, long life and a sea of bitter tears. Just the previous autumn, Mademoiselle de La Valliere has shone as Amazon rider on the hunt. Only a few months later the change was overpowering. “That’s where loving a man can bring a woman” Angélique thought. Her anger flared again.

(Golon, Sergeanne. Angélique and the King. London: Pan Major, 1963, p. 162)